It is a commonly heard in casual remarks on gardening topics and maintaining a landscape in the Sierra Foothills that Manzanita and other chaparral plants must be cut down and removed because they are so very flammable.

Yes, it is important to clear 100 feet of defensible space around your home, and yes, Manzanita can act as a ladder fuel, in other words, if left too close to taller trees, fire can jump from the ground up, using medium sized plants as ‘ladders.’

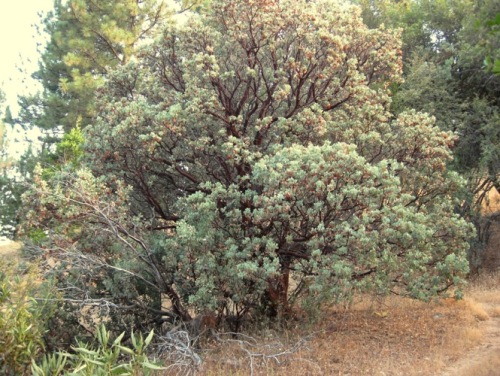

However, yes, it is possible to enjoy growing and caring for your beautiful native manzanitas. The gorgeous burnished red of the bark, the delicate pale pink flower cluster and the flat round grey-green leaves of our native Arctostaphylos viscida or Sticky Whiteleaf Manzanita can be enjoyed under the proper conditions. If left in the garden as accent plants such as the one in the photo, it can be as safe as any plant or tree in the garden. If dead branches are removed, that’s even better.

There are several reputable organizations of professionals that would change the prevalent conception that chaparral plants such as manzanita and our bear clover are indeed more flammable than other plants.

According to Neil McDougald, former Coarsegold Resource Conservation District Director, “The concept of fireproof’ plants is essentially a myth for the Sierra Foothills. Almost all plants will burn given the right conditions. Referring to a plant as “firesafe” means that it tends not to be a significant fuel source by itself. Certain plants may be a poor fuel source because they don’t contain a lot of woody material, or they tend to grow in low densities, or their chemical composition actually resists heat and combustion.

Besides those specific characteristics, one must also consider two other factors: the distribution and the maintenance of the plants. A good example is manzanita. While most people cringe at the thought of a fire ripping through a manzanita thicket, the shrub itself is actually fire resistant. The key is to keep a wide distribution between individual plants and to regularly remove the dead material that accumulates on the plant. A healthy, green manzanita, with five to six feet of clearance around it and no dead branches is very likely to survive a low to moderate intensity fire. Some low-growing species of manzanita are recommended because of their drought tolerance and fire resistance.”

A second quote is from the California Chaparral Institute in answer to the myth that Chaparral plants are full of resinous chemicals which make them more flammable than any other plant.

They say, “Chaparral plant species are NOT “oozing combustible resins” or “born” to burn.”

“Such comments are frequently seen in articles about fires in chaparral, giving the impression that the reason chaparral shrubs are so flammable is primarily due to the presence of flammable chemicals, waxes, or oils in their leaves and stems. While it is true some chaparral plant species (and many other drought-tolerant plants including pines) have aromatic chemicals within their tissues, this does not mean that’s why they ignite or burn so hot when they do. Chaparral plants ignite and burn hot when the environmental conditions are right, namely high temperature, low humidity, and low fuel moistures (the amount of moisture in the plant). In addition, the leaves and stems on many chaparral shrubs are quite small, creating perfect burning conditions – a lot of surface area and space for oxygen. Chaparral shrubs burn so easily because they provide fine, dry fuels during drought conditions. While plant chemicals are certainly involved in the burning process, they do not really make a significant contribution to the flammability of chaparral in general. This also explains why it is usually quite difficult to get chaparral to burn in the spring. There’s too much moisture in the plants. If “oozing combustible resins”* were the main cause of flammability, chaparral would burn easily during any season.”

”*The hyperbolic “oozing” quote came from the July 2008 issue of National Geographic. Being “born to burn” was a comment made by a member of the San Diego Board of Supervisors when justifying the need to conduct large scale prescribed burn programs in the back country.”

These two statements are confirmed by Sabrina L. Drill for a third agency, The California Native Plant Society saying in a 2010 report, “Another myth is that most California native plants are intrinsically highly flammable, and that chaparral and coastal sage systems require frequent fire to be healthy. While several Southern California natives do possess characteristics that make them fire-prone, many are actually highly resistant and tolerant of fire and recover quickly after a wildfire, making them excellent choices for a fire-safe landscape.

12 comments