Marlene Dietrich, in her strong German accent, said this in the old movie ‘Grand Hotel’, but plants say it too, in a silent deadly way. Nature has a way of giving certain plants an advantage over the rest. They contain an unfriendly substance that prevents other plants from growing underneath. They want to be alone.

The word allelopathy comes from two Latin words, allelon meaning ‘of each other’ and pathos which means ‘to suffer’. Allelopathy is the chemical inhibition of one plant to another. The chemical can be in the roots, any part of the plant or even in the soil where it affects the growth development of other competitors. Sometimes it means the plants are aggressive enough to crowd out the competition.

Plants already compete for sun, water and soil nutrients and, like animals, even for territory it seems. Their allelopathic qualities are actually controlling or limiting their surrounding environment causing other plants to decline if they are unlucky enough to seed or be planted too close.

Most commonly, California walnuts trees, Juglans californica and Juglans hindsii , and any walnut tree really, have allelopathic effects on plants growing beneath them. The substance produced by walnuts is called juglone. (Ain’t Latin great!)

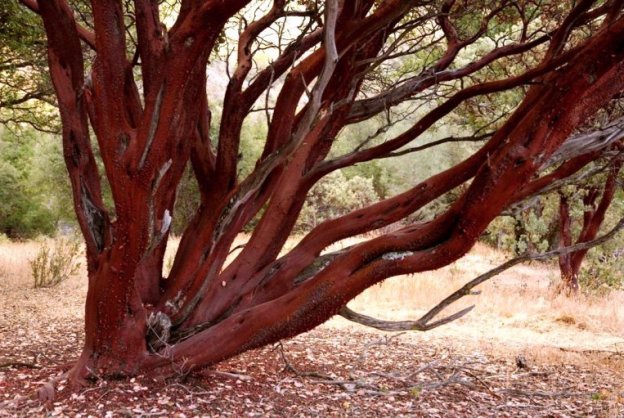

Other trees with allelopathic traits include Bearberry, Oaks, Sycamore, Manzanita California Bay laurel, Cottonwood, Forsythia, Tree-of-heaven, Black locust and Eucalyptus. In my garden, oaks and manzanita, Arctostaphylos viscida, are the ones needing their space, so I don’t plant anything under their canopies.

California chaparral plants, like Brittlebush, Encelia farinose, Purple sage, Salvia leucophylla, California sagebrush, Artemisia californica, and Chamise, Adenostoma fasciculatum have been known to be allelopathic. However, botanists now know that bare zones under chapparal plants are caused by animals seeking cover and, basicly “eating at home”

In the garden, when you discover a tree or shrub is resisting any plants growing underneath, you can begin to work with nature. Raking under a tree or spreading mulch to add neatness can help blend these areas into your scheme. You no longer have to fight it, but plant outside the drip lines of these difficult characters.

Note: If you have eucalyptus and white fly problems you are in luck! Covering the ground, underneath a white fly infested plant, with eucalyptus bark will clear up the problem like magic. After chopping down a Euc, and when the bark on the logs began to dry and flake off, I happened to use the bark as mulch under a hibiscus (this was in Fullerton…Southern California). It had had a bad case of white fly, but after a few months it was completely gone!

garbo: “I want to be alone!”

List of plants for around oaks and pines

Sources:

http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/BT9900245.htm

“It was concluded that allelopathy is likely to be a cause of understorey suppression by Eucalyptus species especially in drier climates.”

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa4017/is_200410/ai_n11850358/

“Plant ecologists generally view the entire concept of allelopathy with understandable skepticism because hundreds of investigations have produced little more than ambiguity. As demonstrated in Muller’s work, ecological variables are notoriously difficult to isolate. In commenting on the need for researchers to recognize this difficulty, John Harper (1975), the prominent plant population biologist from England, wrote, “It would be surprising if, among the variety of plant interactions in nature, there were not cases in which toxins played an important ecological role, but it does not help the discovery of such cases to preach their existence as though it were gospel.”

http://library.ndsu.edu/repository/bitstream/handle/10365/3194/441man85.pdf?sequence=1

“Hydroquinone and arbutin have been considered as allelopathic agents from the aqueous leachates of species of manzanita.”

http://depts.washington.edu/hortlib/resources/resource_search.php?term=1130

“This toxic affect(of Black Walnut) on surrounding plants appears to be related to root contact, as walnut hulls and leaves used as mulch have not shown toxic effects on plant growth…The juglone toxin occurs in the leaves, bark, and wood of the walnut but these contain lower concentrations than the roots.”

7 comments